A holiday in England in December: I shivered at the sheer thought. The temperatures in London the previous week had dipped below zero. That didn’t dissuade me. After all, I had been to Alaska. It can’t be colder than that. I had to be in England soon after Christmas, so why not weave a holiday around it?

Slate-grey skies and a persistent drizzle greeted me in London. Yes, it was chilly but not freezing. Around 10°C. I took the easy option: a tour bus, which took us past some major landmarks. The towering St. Paul’s Cathedral was the first stop. An imposing domed building, Sir Christopher Wren’s masterpiece was constructed between 1675-1710 after the Great Fire of London. It took a while to take in the splendour of the statues and other artworks inside the cathedral.

Next up was the Tower of London and its grisly past of around 1000 years. Built by William the Conqueror in 1066, it was a palace, a notorious prison and an execution site where even queens met their bloody end. They still keep ravens so that the monarchy doesn’t fall (that’s the legend). I gave the Crown Jewels Collection a miss; the serpentine queue was intimidating.

The cruise on the Thames

The evening cruise on the Thames made up for it. Starting near the Tower Bridge, it passed the other spans across the river, and I soaked up the sights before alighting at the Westminster Pier. A short walk brought me closer to the Parliament Building, and Big Ben loomed ahead. The place was teeming with tourists. More walking, there was Horatio Nelson atop a column at Trafalgar Square. Tired limbs called for an Uber ride to the hotel.

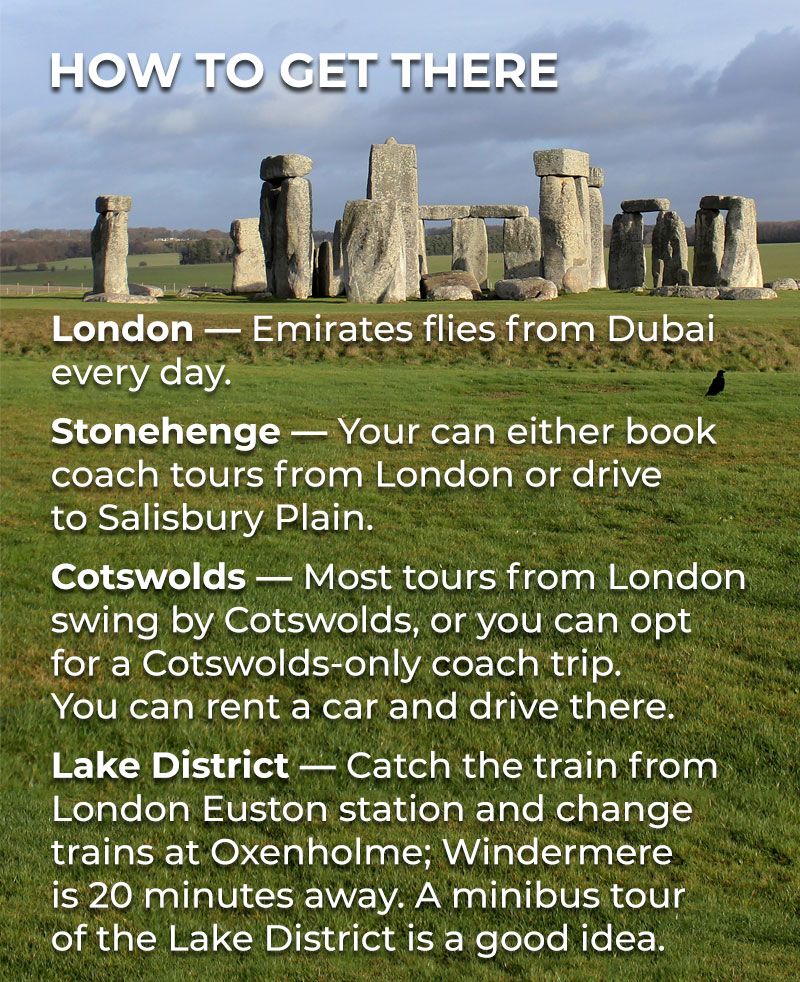

Stonehenge beckoned the following day. A two-hour morning bus ride took us to Salisbury Plain, site of the giant stone circle. The sight of Stonehenge triggered something in me, and I paced around it like a teenager gawking at the massive pillars. Each of the stones was different, some straddling others. It was a sight to behold. Was it a pagan ritual site, royal burial site or an astronomical clock? I couldn’t care. I was chuffed to see them up close.

Cotswolds: villages frozen in time

The Cotswolds region in central-southwest England is a window into the past. The 17th-century villages, spread over 2,000 sq km across six counties, are said to have inspired Lord of the Rings writer J R Tolkien in creating the Hobbit village. We left London behind, and our bus swung past Burford, the gateway to Cotswolds, before pulling up at Arlington Row.

At the start of the path stood a row of conjoined houses with honey-coloured stone walls, chimneys and slate roofs. It was indeed a frieze from the past. Four centuries back, a wool-weaving community lived here. Wool shorn from the heavy-fleeced manes of that reared Cotswold Lions sheep must have been washed in the stream that gurgled nearby, and dried in the large open area beside it. That was until cotton imports from India killed the wool industry.

Arlington Row turned out to be the best of the Cotswolds. Bibury, Bourton-on-the-Water (the Windrush river runs through it) and Stow-on-the-Wold were bustling towns. The honey-hued limestone buildings with slate roofs and cobbled streets were beautiful, but I had expected them to be more serene. So I strolled past the shop-lined streets to find meadows and picture-perfect houses. I came away thinking there’s more to Cotswolds than what I saw.

Time to head northwest of England. An afternoon train from London Euston station took us to Oxenholme, where we changed trains to Windermere.

The Lake District had lingered in my imagination since schooldays when William Wordsworth and his poem Daffodils came into my world. Later I learned of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and John Keats too. Not sure about P.B. Shelley. I never came across Beatrix Potter. Maybe, by then, I was too old for her books.

I did find a Beatrix Potter souvenir shop during an early morning trip to the town of Bowness-on-Windermere. After a 20-minute walk, I stood gaping at Lake Windermere: the largest (15 sq km) lake in England.

The grandeur of Lake District

Lake Windermere gets its name from the Viking Vinandr, and mere means a body of water. It looked cold, icy and stark. Dark clouds hung over the lake and the landscape looked like a still from a black-and-white movie. The coniferous tree forest across the lake and the tiny island was devoid of colour, and the water in the distance looked snowy white. Yet, there was a grandeur.

There was more come the following day: a 10-lake tour. The Sun made a rare appearance early morning, and there was a warm glow, although the temperature was 1°C. Our minibus climbed through narrow, steep roads of the Lake District, which has 16 lakes and more than 6,000 archaeological sites where the Vikings, Romans and Anglo-Saxons left their mark.

The Viking influence

Many Norse traditions are still alive: the most evident one is the drystone walls (built with small slabs of stones and no binding material like mud or mortar). Many place names reveal their Old Norse roots: dale for the valley, fell means hill or mountain, beck is a stream and gill a ravine.

The bus wound its way through the Kirkstone Pass on Ambleside, and a huge vista opened before us. We stopped at a clearing with mountains all around, and the valley pointed to Brothers Water Lake in the distance. It was spellbinding. No words could describe the beauty.

Passing through Patterdale, we reached Glenridding and came upon Ullswater Lake, the second largest water body (9 sq km) in the district. The lake where Donald Campbell drove his boat Bluebird at 202.32mph to set a water speed record in 1955.

Land of stone circles

We soon arrived at the Castlerigg Stone Circle. It’s not on the scale of Stonehenge, but much older. Around 5,000 years old, Castlerigg, with 38 large stones (some are 3 metres high), is the most famous of the 50 stone circles in the Lake District. Like all stone circles, its origins remain a mystery.

Leaving the mystery aside, we headed towards Keswick. Surprise View in Borrowdale was stunning. It’s on a mountain overlooking Derwentwater Lake, and the sight was gorgeous, with the dry ferns giving a reddish hue to the rolling mountains.

We soon entered the A591 motorway, which links Keswick, Grasmere, Ambleside and Windermere. It was easy to see why it was voted the most scenic route in England a few years back. Rolling hills and vast expanses of grasslands fringed with drystone walls swept past us as the leafless trees stood starkly against the blue skies with wisps of clouds floating around.

Why are there so many mountains in the district of the lakes? The ice erosion led to the creation of this magnificent landscape. Ribbon lakes and valleys formed when Ice Age glaciers melted, but the hard rocks withstood glaciation and became mountains (Helvellyn mountain is made up of igneous rocks formed 450 million years ago). The pastoral life of the Vikings added to the beauty of the terrain.

Grasmere: the fairest place on Earth

We saw several groups of Herdwick sheep with thick fluffy fleeces that are unique to the central western parts of the Lake District. The hardy animals, reared for meat and wool, were introduced by the Vikings in the 6th century. The name “Herdwyck” comes from Old Norse, the Viking language, meaning “sheep pasture”.

Soon we were in Wordsworth country: Grasmere. William Wordsworth, the poet, called it: The fairest place on Earth. Wordsworth, his sister Dorothy and his wife Mary are all buried in the St. Oswald Churchyard. Grasmere paid tribute to its most famous son with the Wordsworth Daffodil Garden; I looked for daffodils but found none. Instead, I found paved stones inscribed with two stanzas of his poem.

Driving past more picturesque roads fringed with vast plains overlooking mountains, we went past Sting’s house (he was a tutor in the district before the singer found fame through The Police) and the Britannia Inn, where Horatio Nelson stayed before the Battle of Trafalgar. Alfred Nobel, of the Nobel Prize fame, owned a gunpowder mine in the district, I was told, as we skirted the Eltenwater Lake and sped towards Coniston Water, the third largest lake in the district where Donald Campell was killed in 1967 in the waters where he set four successive water speed records.

It was 4pm, and the light was fading fast. After a short stop at the enchanting Tarns Hows, an artificial lake made by joining three tarns, we headed back to Windermere. Which was the best lake? Was it Ullswater or Derwentwater? I couldn’t decide.

We had covered a significant part of the 2,292-sq km national park. It was breathtakingly beautiful. Little wonder, it fired the imagination of the Romantic poets.

Source: Read Full Article