Every August, Toronto's streets vibrate with a familiar island rhythm. The Toronto Caribbean Carnival (also known by its original moniker, Caribana) is an annual event thrown on the anniversary weekend of slave emancipation in Canada. (Yes, we had slavery here, too.)

The lilting peals of calypso steel pans, driving reggae beats, and pulsing hip-hop fill the city streets, and Canadian-Caribbean households ready extra bedrooms for relatives from far and wide. More than half of the estimated two million revelers — of all races, sizes, and dancing abilities — who opt to tek a wine alongside citizens of "The Six" are out-of-towners. They consistently sell out the city's hotels, bars, and restaurants to the tune of more than $400 million every year.

The pandemic crashed the party in 2020, and this summer, the festivities will go virtual. But I'm old enough to remember when the popular parade, which started in 1967 as part of a celebration of the country's centennial, wasn't relegated to the city's lakeshore, as it is now. My parents would pack us kids onto the subway and hustle to find a curb we could perch on along University Avenue — a key hub in the city's downtown core. From there, among friends new and old, we would take in the kaleidoscope of costumes and cacophony of sound.

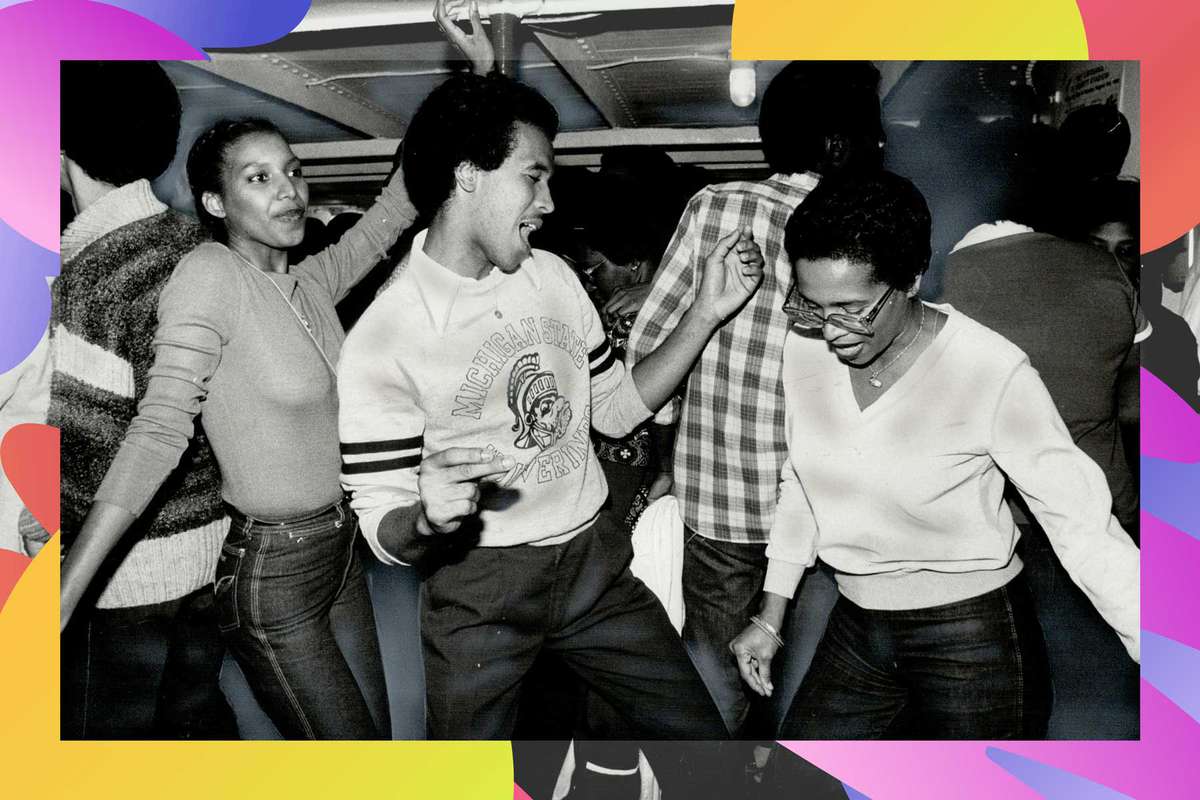

As a teenager, I ditched the parental accompaniment, opting to head out with girlfriends. In fresh kicks and outfits strategically chosen to impress, we'd hop barricades and join the street parade before rushing home to primp for evening parties that went on until long after my curfew. It was a good time. And for years, that reconnection to my Jamaican heritage was enough.

Eventually, I craved more information. I was born in Canada, and despite the quizzical looks I got from Americans as I explained that "Yes, there are Black Canadians," I'd always felt like I belonged here. Still, my connection lacked depth. Black History Month wasn't a thing when I was growing up. (Ironically, its birth in Canada is linked to a Caribbean immigrant, the Honorable Jean Augustine, the first Black female Member of Parliament, who created it in 1995.) I was never taught a Canadian history that included Caribbean contributions as a thread in its founding fabric. But as an adult, I began to search for more — and found it.

The Caribbean Connection

Canada's Caribbean roots run deep, stretching back to 1796, when Jamaican Maroons — escaped slaves who established communities on the island and continued to fight against the British — were deported to Halifax, Nova Scotia. They stayed for four years before, understandably, deciding the cold weather wasn't for them. Immigrants from Jamaica and Barbados followed in the 1800s, coming to work the coal mines in Cape Breton and Sydney.

Several waves of immigration followed. Between 1900 and 1960, 21,500 immigrants from Caribbean countries arrived. In 1955, the West Indian Domestic Scheme, which continued until 1967, permitted Bajans and Jamaicans to enter the country as domestic workers. Many seized on the opportunity, even when their education and qualifications far exceeded that role. In the late 60s and early 70s (the years my family made their way here), there was another boom. In fact, most Caribbean-Canadians in the country today are here as the result of a multiculturalism policy initiated in 1971 by then-prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

Once here, they made their mark. Caribbean-Canadians were instrumental in the fight against racial discrimination that barred Black workers from jobs on the railway, and eventually established the Order of Sleeping Car Porters. And it was Caribbean-Canadians, including historian and author Afua Cooper, former lieutenant governor of Ontario Lincoln Alexander, and Olympian Bruny Surin, who continued that legacy, becoming role models for first-generation Canadians like me.

The Legacy Continues

The generations that followed have pushed forward while reaching back. You hear it in the music that transcends our borders, from Canadian artists such as Kardinal Offishall and Kaytranada; in the words of award-winning playwrights like Trey Anthony; and in the activism of newly elected politicians like Member of Parliament Marci Ien.

Today, we are more than 749,000 strong. We are Jamaican, Haitian, Bajan, Trini, and more. And we are Canadian. We are in the oxtail and curry goat on Eglinton Avenue and the authentic dancehall backdrop for Rihanna's "Work" music videos. We are in the codfish that left Newfoundland in the 1700s and eventually became half of Jamaica's national dish, ackee and saltfish. And we are in the rum and molasses that came back.

So yes, you can come to Toronto for Caribana (next year). But you can also swing your hips on the streets of Edmonton, Alberta, at Cariwest; in North Vancouver at Caribbean Days Festival; and at Montreal's Carifiesta. You can celebrate Bajan culture at Toronto's Barbados on the Water event and appreciate the diversity of our music at the Winnipeg International Soca Reggae Festival. And you can savor Caribbean flavors across the country: Trini stew fish at Antoinette's Restaurant in the city of Whitehorse in the Yukon; black lentil dahl at Trini throwback Baccanalle in Ottawa; and Guyanese curry in fluffy roti shells at Famena's Famous Roti & Curry in Winnipeg. We also shine through on the airwaves, in dance performances, and via stories on film.

We are here. And when you visit, you feel it.

In the lyrical, patois-laced banter in neighborhoods. In the mom-and-pop shops, where bright walls and spicy dishes transport you to the islands. In the Caribbean-flag-embellished clothing on the backs of Canadian kids whose only connections are their bloodlines. We are entrenched in this country's maritime hills and prairie horsebacks, in the bricks that built it and the soil it stands on. And although you may not find us in the streets this summer, you can be sure that as soon as it's possible, we'll be back there, too.

Heather Greenwood Davis is a contributing writer and on-air personality for National Geographic and a freelancer for a host of international publications. Recently, you may have seen her on Good Morning America, CBS Sunday Morning, and The Social. Find her on Twitter and Instagram.

Source: Read Full Article