Like many places, Mammoth Cave—Kentucky’s only national park and the world’s longest cave system—saw its visitation hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2019, more than half a million tourists descended on the 53,000-acre park, but that number fell by half in 2020 to just 290,000. Coronavirus precautions were partly responsible. The park limited its typical roster of almost 20 cave tours to a single self-guided tour, and provided timed tickets to groups of no more than 32 people. (As current federal mandates require, all visitors and employees are masked within federal buildings and the cave system.)

But this year, the continued search for outdoor activities may bring greater popularity to Mammoth Cave National Park—at least according to AirBnB, which listed the area in its top 10 trending destinations in March. Molly Schroer, spokesperson for Mammoth Cave, says one of the main draws for visitors is the diversity of park experiences: 100-plus miles of aboveground trails and riverways for hiking, biking, horseback riding, and paddling, as well as 400-plus miles of limestone labyrinths underground.

Learn more about how to visit Mammoth Cave National Park.

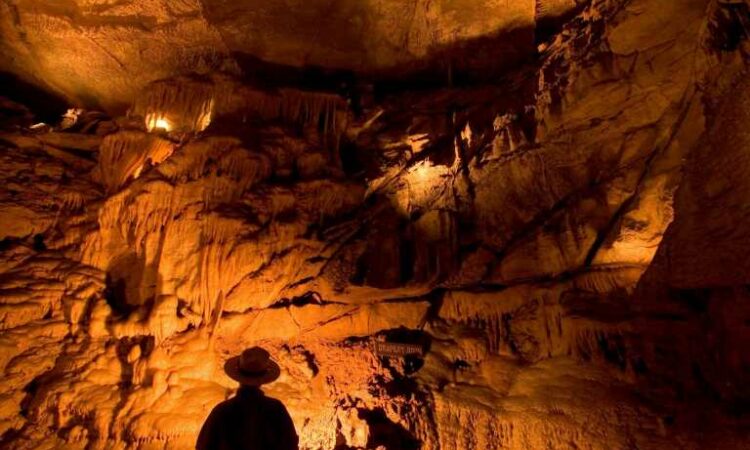

On this year’s only available tour (reservations recommended), guests wander two miles of trail in the cool, shadowed cave, where natural air conditioning issues a steady breeze and temperatures hover around 54 degrees. All the while, interpreters stand ready to tell stories of the cave’s long, colorful history.

The depths of time

Much has changed since humans first discovered Mammoth Cave more than 4,000 years ago. The ancestors of seven tribes associated with historic use of the parklands—including the Cherokee Nation and Shawnee Tribe—once used the cave system to mine minerals like gypsum with mussel shell scrapers harvested from the Green River. They told their own stories in petroglyphs, pictographs, and burials, leaving behind mummified remains.

These cave discoveries suggest people may have lived in America twice as long as we thought.

Bishop was enslaved all the while, only gaining his freedom just prior to the Civil War. Although he chose to stay and work as a paid guide, Bishop once called the cave system he loved “a grand, gloomy, and peculiar place.”

But the importance of Black guides, who worked for a century alongside white cave guides, was diminished when the National Park Service began operating Mammoth Cave in 1941. The federal government chose not to hire any of the park’s Black guides, including those serving for a fourth generation.

Some of these guides were the descendants of Materson Bransford, a son of his own enslaver, who was “leased” to the owner of Mammoth Cave in his early twenties. Materson’s great-great-grandson Jerry Bransford continued his legacy in 2004, when he was hired to work at Mammoth Cave half a century after his last relative left park employment.

The Cave Wars

In the years between those early explorers and the national park we know today, the region was gripped not only by Reconstruction and Jim Crow but also by an upheaval of competition, court battles, and cataclysmic feuds known as the Cave Wars.

By the early 1900s, more than 20 additional caves had been opened to the public. Landowners stood to make more money off tourists than farming. They crowded roadways with giant signs and booths where solicitors—known as “cave cappers” because of their hats—redirected tourists from the world-famous Mammoth Cave to their own lesser known grottos.

Plan an epic road trip to Tennessee’s coolest caverns.

Soon enough, rivals turned their attention to finding a “back door” to Mammoth Cave. When the automobile era started bringing an unprecedented number of tourists to southcentral Kentucky, farmers and landowners jumped on potential profits, descending into legal fights over property rights to caves hundreds of feet below the surface.

But in 1925, the Cave Wars ended tragically when an explorer named Floyd Collins, trying to expand his family’s failing cave business, died after becoming trapped underground. The dangers propelled local property owners to work with federal officials in an already growing movement to operate Mammoth Cave as a protected park; it was chartered the following year.

By the 1960s, the cutthroat competition of earlier decades had been replaced by cross-promotion and reconciliation.

“We learned to work together,” Schroer says. “We cooperate with caves in the area and work together to get people in, because we realize tourism is a big part of south-central Kentucky.”

There’s no way to predict how many visitors Mammoth Cave will see in 2021. But the potential crowds are simply following in the footsteps of those who’ve gone before to marvel at these stunning underground wonders—only this time, with better safety measures.

Source: Read Full Article